Infrastructure-building for Public Health : The World Health Organization and Tuberculosis Control in South Korea, 1945-1963†

Article information

Abstract

This paper examines WHO’s involvement in South Korea within the context of the changing organization of public health infrastructure in Korea during the years spanning from the end of the Japanese occupation, through the periods of American military occupation and the Korean War, and to the early years of the Park Chung Hee regime in the early 1960s, in order to demonstrate how tuberculosis came to be addressed as a public health problem. WHO launched several survey missions and relief efforts before and during the Korean War and subsequently became deeply involved in shaping government policy for public health through a number of technical assistance programs, including a program for tuberculosis control in the early 1960s. This paper argues that the principal concern for WHO was to start rebuilding the public health infrastructure beyond simply abolishing the remnants of colonial practices or showcasing the superiority of American practices vis-à-vis those practiced under a Communist rule. WHO consistently sought to address infrastructural problems by strengthening the government’s role by linking the central and regional health units, and this was especially visible in its tuberculosis program, where it attempted to take back the responsibilities and functions previously assumed by voluntary organizations like the Korea National Tuberculosis Administration (KNTA). This interest in public health infrastructure was fueled by WHO’s discovery of a cost-effective, drug-based, and community-oriented horizontal approach to tuberculosis control, with a hope that these practices would replace the traditional, costly, disease-specific, and seclusion-oriented vertical approach that relied on sanatoria. These policy imperatives were met with the unanticipated regime change from a civilian to a military government in 1961, which created an environment favorable for the expansion of the public health network. Technology and politics were intricately intertwined in the emergence of a new infrastructure for public health in Korea, as this case of tuberculosis control illustrates.

1. Introduction

In October 1961, the South Korean Ministry of Health announced that it had signed an agreement with the World Health Organization (WHO) to launch a five-year program for technical assistance in tuberculosis control, including 125,000 USD in financial support [1,]. Tuberculosis had long been one of the most persistent health problems in Korea, notoriously known as ‘manggukbyoung,’ meaning a ‘disease that will bring a nation to its ruin.’ Following liberation from Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945), the number of tuberculosis patients had increased at an alarming rate. Tuberculosis became the number one cause of death in the late 1940s, killing 100,000 persons annually and infecting nearly one million people out of a total population of twenty million [2,]. Controlling the disease, or launching major public health interventions on the national scale, would require financial resources and technical capacities that the government could not deliver on its own. Amidst public outcry over the deteriorating health and living conditions [3,], the prospect of WHO’s assistance that would follow South Korea becoming a member state in 1949 was seen as a “ray of hope shining on future improvements to the state of the public’s health.” [4] It took more than a decade, however, for WHO to deliver that assistance.

The South Korean government launched its national tuberculosis control program in the following year after signing the 1961 agreement with WHO. But the following questions can be raised: Exactly what role did WHO play in this control program? How did the new program differ from previous efforts? How can we make sense of WHO’s survey mission during the Korean War (1950-1953)? Despite records of WHO’s wide-ranging contributions [5,], the nature of its activities in Korea as a new international organization that emerged after World War II is yet to be further explored. While historical studies by Lee Sun Ho [6,] and Jane S. Kim have examined the early years of South Korea’s relationship with WHO, such as the process of gaining membership and the ideological dimension of public health policy, the scope of their research does not go beyond the immediate post-Korean War years (Lee, S. H., 2014: 99-126; Kim, J., 2012). Similarly, Yeo In-Seok’s article on malaria control under the American military occupation (1945-1948) only alludes to WHO’s role in the following years (Yeo, 2015: 35-65). Ku Mi-Jin has examined the tension between international and local experts about the tuberculosis control program (Ku, 2005) [7], but the historical events that shaped the program itself remain underexplored.

This paper considers WHO’s involvement in South Korea within the context of the changing organization of public health infrastructure in the country during the years spanning from the end of the Japanese occupation, through the periods of American military occupation and the Korean War, up to the early years of Park Chung Hee’s military dictatorship (1961-1979), in order to demonstrate how tuberculosis came to be addressed as a public health problem. Prior to WHO’s assistance, tuberculosis control in Korea was limited to basic administrative activities and intermittent vaccination campaigns by the government, complemented by activities offered by individual medical doctors, international aid agencies and missionaries, or the Korean National Tuberculosis Association (KNTA), a voluntary organization comprised of elite medical professionals. Following WHO’s technical assistance, however, tuberculosis control activities became centralized as the government expanded and mobilized its network of public health centers in order to deliver diagnostic, preventive, as well as curative services to the public.

In this paper, infrastructure refers to an array of institutional, administrative, organizational, and technological setups that are introduced in order to undergird a specific activity, thereby permitting certain kinds of activities while blocking others (Slota and Bowker, 2017: 530). Under this definition, infrastructure is not a fixed or closed system but a dynamic entity evolving around the policy imperatives, technological advancements, and political situations in society. Infrastructure is thus inherently relational and context-dependent. This paper argues that a new approach to tuberculosis control introduced by WHO became part of Korea’s public health infrastructure by reorienting rather than supplanting over a preexisting one amidst the sociopolitical milieu in the early 1960s that worked favorably for such changes.

The two decades immediately following the end of World War II were an important period for international health as well. Immediately after the war, major donors for health such as the Rockefeller Foundation, the US government, and WHO became awash with enthusiasm for the potential of technological solutions (Farley, 2004: 1; Birn, 2014). For instance, the discovery of new vaccines, antibiotics, and DDT opened new possibilities for gaining mastery over diseases. WHO began to launch expensive disease-specific programs such as the Malaria Eradication Program (MEP, 1955) and the Intensified Smallpox Eradication Campaign (1967) (Litsios, 1997; Bhattacharya, 2006), which historian Randall Packard described as having “eclips[ed] all other health programs” (Packard, 2016: 133). The promise of WHO’s techno-centric mass campaigns allowed for the international community to envision a world where communicable diseases could not only be controlled but eradicated altogether (Williams, 1988; Stepan, 2013: 28-30), and placed WHO on the map as the new professional authority on promoting global welfare (Birn, 2009).

Within WHO, however, there also existed concerns towards the long-term efficacy of such techno-centric, disease-focused programs. Critics warned that although the single-purpose “vertical approach,” as it was coined, could yield rapid results for a given health problem, but would only be temporary. As proponents of the “horizontal approach,” they argued that WHO should also invest in tackling “overall health problems on a wide front and on a long-term basis through the creation of a system of permanent institutions commonly known as general health services” (Gonzalez, 1965: 9; Mills, 2005). The two approaches were not mutually exclusive, but tensions escalated between the two camps as strategies became further dichotomized [8,], until the late 1960s when WHO acknowledged that a robust health infrastructure was an important prerequisite to the success of disease-specific programs (Brown et al., 2006). WHO began to stress the importance of ‘integrating’ disease control services into the general health services, and this turn towards the horizontal approach was epitomized by the Declaration of Alma-Ata adopted at the 1978 International Conference on Primary Health Care held in Kazakhstan (Litsios, 2002) [9].

Tuberculosis control followed a similar trajectory whereby governments had traditionally launched vertical programs through sanatoria, and international health organizations launched prevention campaigns following the dissemination of the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine in the mid-1940s (Brimnes, 2007). Anti-tuberculosis drugs were discovered through the late 1940s, but building and running sanatoria was an expensive option and WHO recognized in as early as the mid-1950s that a vertical approach to tuberculosis control would not be economically feasible in developing countries. In an effort to deliver treatment to large numbers of the population in a cost-effective manner, WHO developed and disseminated the ‘community approach,’ a method which premised on the establishment of centralized networks of public health infrastructure as a prerequisite for disease control (Amrith, 2006: 149-165; Brimnes, 2016: 183-241).

Drawing on previously unexamined archival resources, such as field reports produced by WHO expert consultants and advisers, this paper argues that the principal concern for WHO was to start rebuilding the public health infrastructure beyond simply abolishing remnant colonial practices or showcasing the superiority of the American practices visà-vis those practiced under communist rule. Rather, WHO’s objective was to disseminate the community approach to tuberculosis control—a centralized, cost-effective and techno-centric solution—and by extension, the horizontal approach, which was implemented in South Korea as a result of negotiations and adaptations with the pre-existing infrastructural and political affordances of post-liberation Korea.

2. “The Most Serious Public Health Problem”

In early 1950, Erkki Leppo, a Finnish pediatrician and WHO consultant, arrived in South Korea to carry out a project on mother and child health [10,]. At the time, WHO had plans for subsequent projects for tuberculosis and leprosy control [11,]. Presumably intended to provide background information for these upcoming projects, Leppo drafted a thirty pages-long report in April that year entitled “Tuberculosis in South Korea” that surveyed the availability of treatment, training, and laboratory facilities, along with various local estimates on tuberculosis prevalence, number of patients, and deaths [12,]. Leppo’s report, the first WHO document to highlight the problem of tuberculosis in South Korea [13,], provides a glimpse of the state of tuberculosis immediately prior to the outbreak of the Korean War as “the most widespread of all diseases in Korea [forming] the most serious public health problem in the country… greatly sapping the vitality of [the] nation.” According to his sources, it was estimated that the annual economic losses due to tuberculosis and malaria surpassed the national budget [14].

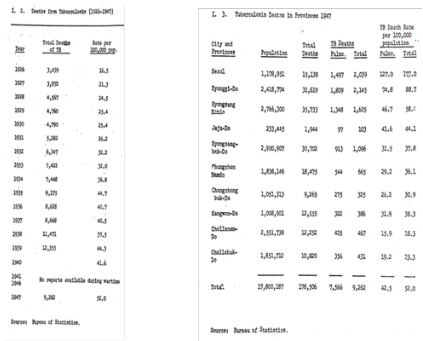

To illustrate the seriousness of the tuberculosis problem, Leppo provided various statistical information. He presented various types of data, including some basic death counts due to tuberculosis dating back to the mid-1920s, as well as more contemporary data (mostly collected in 1947) which were comparatively more intricate (Table 1). For instance, the number of deaths were closely monitored by province, sex, age, and type of tuberculosis (depending of which part of the body it affected); data on prevalence used both Mantoux skin tests and pulmonary X-ray, and were categorized into rates found among orphans, schoolchildren, college students, industrial laborers, and office employees. However, in the first line of the report, Leppo remarked “no statistics concerning the incidence of tuberculosis are available as this disease has never been included in the list of reportable diseases.” Then where did these numbers come from, and who collected them?

By “statistics concerning the incidence of tuberculosis,” Leppo referred specifically to the number of new patients diagnosed with tuberculosis each year, but it was also true that the government did not collect general tuberculosis-related statistics in a systematic manner. A closer consideration of the report reveals Leppo received the data from three different sources: the Ministry of Health, monthly reports of the Bureau of Statistics, and Dr. C. S. Cho, a former professor of radiology at the Seoul National University Medical School. Data marked as having been provided by the authorities included information such as vital statistics (markedly, number of deaths), and inventories of hospital beds and X-ray machines. Information that could more clearly reveal the toll of the disease on the public, such as the results of chest X-ray surveys or Mantoux skin tests, had been provided by Dr. Cho. In other words, the government did not operate a means for collecting national epidemiological data on tuberculosis, but as scattered and incomplete as it may have been, there did exist an administrative infrastructure that was engaged in minimal disease surveillance activities.

At the time, the administrative body overseeing matters of public health was the Ministry of Health, but South Korea’s public health infrastructure under the Rhee Syngman administration (1948-1960) was in flux, both conceptually and bureaucratically. Most Koreans were unfamiliar with the concept of public health, bogeon (保健), which had been introduced by the American military government as the organizing principle of health-related matters in place. Until then, wisaeng (衛生), literally meaning ‘to guard one’s life,’ had been the guiding principle. Traditionally, it was associated with daily aspects of keeping oneself physically healthy, overcoming sickness, and maintaining housing and environmental cleanliness, and later came to serve as a term corresponding to sanitation or hygiene. When the Japanese colonial authority annexed Korea in 1910, it adopted wisaeng as the guiding principle in its health administration, and established the Department of Wisaeng. The wisaeng administration intervened in all matters related to health, such as the management and control of epidemic diseases, vaccinations, sanitation, waterworks, burials, drug control, and health professionals and personnel. The colonial wisaeng administration, however, was distinct in that it stressed on legal enforcement and punitive action against defaulters. The Department of Wisaeng was placed under the Bureau of the Police, and the brutal and coercive activities of the colonial sanitation police were justified under the disguise of enlightenment, modernity, and civility. Wisaeng, in other words, was a demonstration of the ultimate power and regulatory nature of the colonial state that aimed to surveille and govern the daily lives of the public. (Shin, D., 1997: 50, 325-332; Park, Y., 2005: 29-30, 330-372) [15].

Following liberation in 1945, wisaeng was swiftly superseded by the introduction of the term bogeon, when the American military government in South Korea took immediate action to decouple health care administration from police operation. Under Ordinance No.1, its very first exercise of governing power, the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) decoupled health work from police work by abolishing the Department of Wisaeng and established the Bureau of Public Health (although still keeping the term wisaeng in the bureau’s Korean nomenclature). Over the course of the following year, the Bureau underwent a series of renamings and restructurings, culminating in its elevation to Ministry of Public Health and Welfare and officially introducing the term bogeon into the bureaucratic organization (Shin, J., 2000).

The Ministry of Public Health and Welfare assumed the responsibilities of the colonial sanitary police, but it no longer emphasized on punitive sanitation police work. Instead, it launched new programs, notably for training and education of medical and nursing personnel, and established national research laboratories. These programs contrasted with comparative colonial efforts in that opportunities for training, education, research, and governance were open to Koreans. (Park, B., 2005; Kim, Y., 2011; Shin, Y., and J. Seo, 2013; Yeo, 2015).

Another characteristic of the bogeon administration was that it promoted the provision of basic healthcare services through private practice physicians (Shin, O., 1989: 92-93; Shin, J., 2000). This approach to public health was in fact instrumental for Cold War ideological propaganda and emphasizing the superiority of American ideals of democracy and liberalism [16]. As Military Governor of South Korea, Lieutenant General John Reed Hodge stated in a public speech he gave in 1946 while commemorating the first anniversary of the American military government:

We have been running hospitals and medical facilities, educating professionals capable of managing these medical facilities and supplies, and producing a large quantity of drugs based on the Korean people’s science and technology. We’re fighting against cholera with these Korean-produced drugs. We did not issue revolutionary statements or decrees in order to force subjugation. That kind of coercive method seems to produce impressive quantitative results but it is unsound and unjust as it is not based on the representation of the people’s will [17]. Foregrounding political ideology, General Hodge undermined the progress being made in North Korea, while also diverting the attention away from the slow progress in South Korea’s public health sector.

In reality, the lack of medical manpower and health facilities left the country with a dysfunctional network that could not fulfill its functions. Furthermore, the private practice-centered system continued to exacerbate two well-known problems during the colonial period—the urban concentration of physicians and the concomitant increase in the number of villages without doctors. Benefits of modern medicine were not equally distributed. Most visibly, public hospitals in the province had to cope with the loss of their entire Japanese medical staff right after liberation, a problem that had created a huge hole in basic hospital operations. The American system of health care, notable for its division of labor between the state assuming the task of public health administration and voluntary organizations and private practitioners providing health services, was introduced in South Korea amidst these mounting problems (Shin, D., 2015: 100-103).

To make matters worse, when President Rhee took office to succeed the American military government in August 1948, he abolished the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Social affairs absorbed its functions. This downgrading of the healthcare administration into a single bureau reflected the new government’s intention to focus narrowly on key strategic sectors, namely in economic, social, and military affairs. This administrative change, however, only invited protests and uproars from medical professionals and associations. In March 1949, the government restored order by reversing its decision and re-establishing the Ministry of Health, but it faced yet another challenge of shortage of health manpower resulting from the departure of American military medical staff (Shin, D., 2015: 103-104) [18].

Under these circumstances, the tasks required for tuberculosis control were abound, but there was little for Leppo to comment on besides emphasizing the urgent need to launch a national tuberculosis program with the help of international organizations. However, while providing some basic recommendations (such as expanding tuberculosis work in existing health centers and providing better technical training for health workers) [19,], Leppo also inadvertently depicted how ‘vertical’ the feeble but existing programs in Korea were at the time. He noted that despite the Ministry’s plans to develop provincial health centers, “there [were] no modern tuberculosis dispensary services yet developed” in the country [20,]. In addition, the government sought to isolate patients in hospitals and sanatoria, but due to the poor financial conditions, was considering provisions of “simple cottage hospitals” instead [21].

It is plausible that the Korean government at the time was more familiar with the vertical approach for controlling communicable diseases, because it had gained the experience of operating tuberculosis sanatoria throughout the Japanese colonial period (Park, 2013; KNTA, 1998: 306). In addition, there were also a number of leprosaria, both public and private, throughout the country (Kim, J., 2012) [22,]. The South Korean government’s interest in sanatoria until the early 1950s can be observed in a report the Ministry submitted to WHO’s Western Pacific Regional Committee, which South Korea was part of. Under the title ‘Tuberculosis Control,’ the Ministry explained that although three sanatoria were currently in operation [23,], they could only provide 600 beds, but it hoped to secure more beds in the near future “when North Korea is reoccupied… [and] the sanatoria existing in Pyong Kang and Haeju can be rehabilitated and expanded.” [24,] The same report, on the other hand, addressed the matter of general health services through health centers only briefly towards the end of the report. Amid the hostilities of the Korean War, there were only eleven health centers operating throughout the nation, and were considered necessary only insofar as preventive programs were concerned [25].

This was indeed a formative period for post-colonial public health in South Korea. While a decolonization process was underway with the conceptual reorientation from wisaeng to bogeon and the bureaucratic removal of police forces from health affairs, the principles of the American health care system—especially its ideological stance against socialized medicine—came to pervade the administrative infrastructure that was as yet far from being fully functional. Leppo described tuberculosis as “the most serious public health problem” for South Korea, when in fact the most serious problem was the nation’s public health infrastructure itself. Without political and financial support from either the military or the new government, the impact of the bogeon administration on health services were highly limited.

3. The Macdonald Report: Calls for Rural Health Units

Despite its much-awaited arrival, WHO’s assistance was brought to a halt within just a few months when the Korean War broke out and Leppo and his team were evacuated to Japan [26,]. WHO Director-General Brock Chisholm described the situation on the Peninsula as “a most tragic event” of the year befalling WHO and the international community [27,]. WHO put its independent activities on hold, and began to contribute through providing relief, but it no longer liaised directly with Korean officials. Rather, it coordinated its activities with the Civil Relief in Korea (CRIK) program. CRIK was answerable to a military unit known as the United Nations Civil Assistance Command Korea (UNCACK) [28].

The fact that WHO no longer communicated directly with the Ministry but CRIK, a foreign military organization, reflected where the interest for public health lied during conflict. The wartime civil relief program invested little resources on public health infrastructure. Its activities focused instead on short-term relief, such as preventing starvation and controlling epidemics, especially among the refugee population in Daegu and Busan. Although they managed to make some headway, specifically in introducing mass immunization schemes and sanitation projects such as chlorination of wells, insect control, and DDT application, these activities were intended for the military, not for civilians. For instance, the military confiscated wholesale drugs and dressing equipment, occupied hospital buildings, and drafted doctors. To make matters worse, the health authorities were under-equipped, unmanned, disorganized, and overwhelmed. They failed to monitor the spread of smallpox and typhoid within refugee camps, and could not distribute medical supplies or recruit medical personnel. People in large cities had been better off until then as they could seek care through private practice physicians, but even these doctors could not provide treatment due to limited supplies as a result of to sharply rising costs [29].

Meanwhile, the United Nations Korean Reconstruction Agency (UNKRA, 1950-1958) attempted to rehabilitate the public health infrastructure [30,]. Unlike the civil relief program, UNKRA’s mission was to plan ahead for long-term rehabilitation and reconstruction of the sectors devastated from the war [31,]. As its organizational structure shows, this agency operated a diverse range of programs. Under the Office of the Agent General, the governing office, there were five separate operations sections that oversaw projects in the industrial, mining, education, and housing sectors, with a fifth section reserved for “special projects.” [32,] Under the special projects, UNKRA pursued health-related activities. It provided mobile clinics that could deliver medical and dental services to rural populations [33,], supported the Scandinavian countries’ mission with medical education, and provided programs for physical rehabilitation for those injured during the war [34,]. UNKRA addressed the issue of health infrastructure in earnest in 1952, when it launched the ‘Five-Year Programme for the Rehabilitation of Korea’ as hostilities between the two Koreas seemed to have reached a stalemate [35].

While economic rehabilitation was its main objective, UNKRA also recognized the importance of social rehabilitation—in public health, sanitation, medical care, education, community organization, and labor conditions—in ensuring economic stability. UNKRA worked closely with other agencies within the UN, such as the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and the UN Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Similarly, UNKRA requested WHO to recruit a team of experts in public health for a joint ‘WHO/UNKRA Health Planning Mission in Korea.’ In response, Director General Chrisholm appointed three experts [36,], each bringing distinct specialties and experiences—George Macdonald, W. G. Wickremesinghe, and W. P. Forrest. Their task was to survey the country and recommend programs that should be implemented over each fiscal year for the next five years in the order of relative priority [37].

Macdonald and his team arrived in Korea in early August of 1952, and spent three months travelling across the country visiting hospitals, sanatoria, health centers, medical schools, laboratories. They had meetings with experts working with international organizations and with government officials and health workers. Their findings were presented in a 105-page report, also known as the Macdonald Report, which provided detailed descriptions of their observation under seven headings: organization and administration, public health dispensaries, health statistics, public health activities, medical care, education, and supplies and financing. In a brief opening chapter that summarized the team’s immediate, long-term, and later-term recommendations, the report strongly emphasized the need to urgently address the issues of epidemic and endemic disease (especially parasitism, tuberculosis, and venereal diseases), and provide training for health workers. For the long-term, it prescribed that the government must reform the organizational structure of the public health offices, and more importantly, expand the functions of health dispensaries towards establishing a system of local health units [38].

This set of recommendations was in essence to address the fundamental problem of deplorable healthcare delivery, reflected in the absence of coordination between the central offices and local health services. This lapse in administrative coordination, which the report described as “a complete break in the channel of technical responsibility” [39,] was largely attributed to the confusion brought on by the two major accounts of administrative restructuring after 1945. First, the American military occupation’s decision to decouple health activities from the Police Bureau and reassign the responsibilities to Provincial Bureaus of Health and Welfare, which could be seen as part of the decolonization process, officially authorized the local administrators to oversee health activities. In reality, however, the police departments continued to execute their old health functions, rendering the Provincial Health Bureaus ineffectual. Second, although the Rhee administration’s downsizing of the Department of Public Health and Welfare was quickly reversed to re-establish the Ministry of Health, the reversion was not reflected at the local level. The Provincial Health Sections remained under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Social Affairs rather than being transferred to the Health Ministry [40].

Another major structural problem was the lack of local health centers. The Macdonald Report strongly suggested that more health units should be established across the country to carry out local health work. In fact, the government had established in 1951 roughly 500 health dispensaries, 400 of which were located in rural areas. But due to the shortage of staff, resources, and systemic planning, their activities were limited to providing very basic medical care and immunization. The report recommended that these dispensaries be converted into health units, and that the appropriate health administrators, doctors, nurses, and medical staff be trained to support these health units [41].

The third topic that the report stressed was the problem of tuberculosis. Under the title of “Diseases of Major Social Importance,” it listed four diseases—leprosy, venereal diseases, parasitic diseases, and tuberculosis— that had significant implications on the nation’s economy and required systematic planning over extended periods [42,]. Among them, tuberculosis stood out as the one for which “an urgent request should be made to the World Health Organization.” The long-term goal was to integrate tuberculosis control into the general health services, but Macdonald’s team was skeptical of the government’s financial and technical capacity to undertake a full program on its own besides immunization campaigns [43].

The core message of the Macdonald Report was that a network of health units should be made in the public health infrastructure. The report encouraged the South Korean government to pursue a centralized network of rural health units buttressed by a strong line of communication between the Ministry and the Provincial Bureaus, as they had proven their effectiveness in “many countries,” including Ceylon where W. G. Wickremesinghe was serving as the Director of Health Services [44]. In sum, WHO’s recommendation was to expand the government’s responsibilities towards a more centralized yet more broadly networked approach to public health.

4. Voluntary Health Organizations as Part of Infrastructure

While the government struggled to reinforce its infrastructure during the 1950s, one source of international medical assistance was the Scandinavian Medical Mission, a collaborative project between Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. The three countries’ health work in Korea began when they launched medical relief work following the outbreak of the Korean War. They catered to the medical needs of the Unified Command, respectively, but their representatives began discussing possibilities of a joint, post-war medical effort from as early as 1951 (Park, J., 2010). This came to fruition in 1956, when a three-party agreement was signed between the Korean government, the Scandinavian Mission, and UNKRA for the establishment of a National Medical Center (NMC, 국립의료원). The Korean government purchased the building that had once housed the Seoul City Hospital (서울시립시민병원), and the Scandinavian Mission and UNKRA donated a matching fund of approximately two million dollars each [45,]. Located in central Seoul, the Medical Center was a fully equipped modern hospital, and opened its doors to the public in 1958. It not only provided free treatment for tuberculosis patients but carried out surveys and case-finding programs in the neighborhoods close by, acting as a standalone health unit for the nearby communities [46].

Another major influential source of international assistance was the American-Korean Foundation (AKF). Founded in response to the outbreak of the Korean War, AKF was a non-governmental, non-profit organization, yet carrying the political and capitalist interests of the U.S. Its mission was to supplement the government’s foreign aid policy with social agendas, spread American ideals to Korean people, and support their socioeconomic activities as not only humanitarian work but part of the war against poverty and communism in the Far East [47,]. The Foundation launched two survey missions in 1953, each followed by a wide range of projects for the postwar reconstruction of public health infrastructure (Kwon, 2017: iii) [48]. Although the lion’s share of the Foundation’s health projects were focused on physical rehabilitation programs, it recognized the urgent need for controlling tuberculosis in the country.

The American-Korean Foundation supported the Korean government for hiring a tuberculosis expert to work in the Ministry of Health with an initial donation of 10,000 dollars. In September 1953, the Ministry was able to appoint Han Eung Soo, a recent returnee from the US, to head the newly organized Tuberculosis Controller’s Office. Having studied bacteriology for four years at Duke University on a WHO fellowship, Han was familiar with the American approach to public health and tuberculosis control. He also had a wide social network within the South Korean medical and public health community. Well-connected and fluent in English, he was deemed an ideal person to serve as the liaison between AKF and the Ministry (KNTA, 1993: 338-341; KNTA, 1998: 979-980). As head of the Tuberculosis Controller’s Office, Han was also in charge of overseeing the training of tuberculosis personnel, providing health education to the public, organizing mass surveys for disease surveillance, mass vaccination campaigns, and popularizing the ambulatory treatment system. Day-to-day operations were carried out through another institution newly established with the Foundation’s funding—the National Tuberculosis Center, for which Han also acted as director [49].

The American-Korean Foundation initiated another notable tuberculosis project by supporting the establishment of the Korea National Tuberculosis Association (KNTA). Since liberation from colonial rule in 1945, several voluntary organizations for tuberculosis had sprung up among different medical circles, but they all dissolved with the outbreak of the Korean War. In 1953, members of these groups reassembled to form a voluntary organization. From the outset, the Association had close ties with the Ministry and the Foundation, which provided 1,000 dollars as seed money to cover expenses for the first year. Han Eung Soo was also a founding member, serving as the Association’s Executive Secretary (Kwon, 2017: 58) [50].

With the Foundation’s support, the Association embarked on programs that would enable its self-sustainment. It immediately launched the Christmas seal campaign, which became a major source of funds on which the Association relied over the next several decades. It also began to publish a series of periodicals: Bogeon Segye, a magazine for public education, and Kyulhaek, a technical journal for tuberculosis experts. It furthered its academic contribution by regularly organizing academic conferences, and also became a member of the International Union Against Tuberculosis (IUAT). Furthermore, the Association expanded in size and coverage throughout the late 1950s, establishing branch offices across the nation. By the end of the decade, the Association’s headquarters operated 10 branch offices, several equipped with a clinic (KNTA, 1974: 65).

Over the course of three years, the Association was the largest beneficiary of the Foundation’s donations for tuberculosis, receiving 24,000 out of the Foundation’s total contribution of 45,000 dollars (Kwon, 2017: 56). This substantial support and the close relationship forged between the Association and the Controller’s Office were not by chance. In fact, it closely resembled the American system of tuberculosis control. The division of labor between the Association and the Tuberculosis Controller’s Office was similar to the one between the public and private or voluntary sectors in the US. The Controller’s Office was in charge of planning and surveillance, or administrative and diplomatic matters, whereas technical operations and delivery were delegated to the Association [51].

The Foundation’s activities in Korea lasted only two years between 1953 and 1955, but its policy decisions affected how tuberculosis was controlled, and by whom, for the rest of the decade. The Ministry took a backseat, providing administrative support, while KNTA assumed technical operations on the field. In 1955, the Ministry launched a 5-Year Anti-Tuberculosis Plan for public education, case-finding, prevention, treatment, personnel training, and nation-wide prevalence surveys. For all six measures, the Ministry relied on the Association for its technical capacity. The Association’s branch offices provided tuberculosis services to local residents, as public health units recommended by the Macdonald Report had yet to be created. Moreover, with the decision to close down the National Tuberculosis Center in 1958 because of the increasing financial burden on the government at the end of the Foundation’s support, the Association took up the Center’s responsibilities of case-finding, treatment, and education (KNTA, 1998: 390-395, 409-411).

In the 1959 Annual Report on Tuberculosis Control published by the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, the Ministry credited the Association for its “compliance with the Ministry’s tuberculosis policy and anti-tuberculosis activities through its local branches” and “hoped for more active” operations from the Association in case-finding, prevalence surveys, and free treatment services [52]. This arrangement of delegating public activities of tuberculosis control to voluntary associations was a temporary measure at a time when the government still did not have an administrative capacity to purse the recommendations made in the Macdonald Report, but as such, it carried the momentum into the 1960s.

5. The 1962 Plan of Operations: Centralizing Tuberculosis Control

Towards the end of the 1950s, tuberculosis control in South Korea faced several setbacks. AFK discontinued its health program in 1955; UNKRA was abolished in 1958; the National Tuberculosis Center closed the same year; and subsequently, the Tuberculosis Controller, Han, resigned from his post [53,]. Drastically downsized was direct support from the U.S. government, which had totaled over two million dollars in drugs and equipment for tuberculosis provided through the US Overseas Mission in Korea (USOM-K), Foreign Operations Agency (FOA), and International Cooperation Administration (ICA) [54]. Meanwhile in Geneva, WHO’s international disease control activities were marked by a rising confidence in technological solutions. The Malaria Eradication Program in 1955 and the announcement of the proposal to eradicate smallpox in 1959 epitomized its techno-centric approach to international health problems.

Tuberculosis, however, had not been one of WHO’s early interests as it was considered a social disease that would require state-level planning for longer-term reform. Until the acceptance of BCG vaccine in the mid-1940s and the discovery of the ‘magic bullet’ streptomycin in 1943, developed countries adopted the vertical approach of prevention and treatment limited to segregation and bed in sanatoria. In developing countries that could not afford to build sanatoria, vaccinations were the only feasible method of systematic control [55,]. But in the mid-1950s, WHO carried out a series of pilot programs and clinical trials in Kenya and India, in search for an effective, simple, and affordable alternative to the expensive streptomycin (Valier, 2010; McMillen, 2015: 119-137; Amrith, 2006: 149-160; Leeming-Latham, 2015: 156-176). In 1959, WHO presented the outcomes of a study that promised all three. Published in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization and Tubercle [56,], results from the Tuberculosis Chemotherapy Center in Madras, India, showed that patients treated with a combination of two new drugs—isoniazid and PAS, both of which could easily be taken orally from their own homes—made the same progress as those treated in isolation at hospitals. This was a feat for tuberculosis chemotherapy. Domiciliary chemotherapy meant that the government did not have to spend money on building and maintaining hospital beds, and that healthcare personnel could be replaced with low-skilled auxiliary workers (Raviglione and Pio, 2002: 776). WHO later noted that these “outstanding” outcomes of the Madras study, “more than the actual discovery of the drugs themselves, [were] the real breakthrough.” [57,] Later that year, WHO’s Technical Committee on Tuberculosis presented the “community approach” that would form the basis of its National Tuberculosis Programmes (NTPs); tuberculosis was a community problem that must, and now could be, addressed within the communities, rather than an individual’s problem to be treated at a sanatoria outside of the community [58].

It was against these backdrops that WHO resumed its public health projects in South Korea, including a survey for a tuberculosis program. The community approach was introduced to Korea by J. C. Tao, a tuberculosis expert for WHO’s Western Pacific Regional Office (WPRO). Upon the Korean government’s request for technical assistance in tuberculosis control, Tao arrived in Seoul in March 1961 for a week-long field visit to assess local public health and tuberculosis activities and discuss possible areas of cooperation. After this trip, he submitted a 20-page report of his observations and recommendations. Tao stated, like Macdonald and Leppo before him, that tuberculosis was “the most serious and probably the most important communicable disease problem in the Republic.” Reliable statistics were still unavailable, but based on a tuberculin survey carried out in 1958, over 90 percent of a sample of adults reacted positive (meaning infected with tuberculosis). He found that resources for tuberculosis in Korea were rather favorable compared to other parts of the world, but the lack of a central coordinating committee resulted in low uniformity and inefficiency. In addition, the administrative authority was still divided between the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs and the provincial health offices, as local health remained under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Education and Social Affairs. A large part of Tao’s report gave a detailed observation of technical aspects of tuberculosis control, but his primary recommendation was about the administration. He advised that, first and foremost, a ‘Tuberculosis Control Body’ be established within the Ministry, and that the provincial government be reinforced with personnel such as medical officers, technicians, and nurses [59].

Later that year, WHO drafted a “Plan of Operations for a National Tuberculosis Control Programme in the Republic of Korea,” which outlined the terms of a five-year program financed by an emergency fund from the UN’s Expanded Program for Technical Assistance. The Plan laid out four short-term and two long-range objectives: in the short-term, to establish an administrative body within the Ministry to oversee tuberculosis activities, reinforce provincial level programs, train a wide range of personnel, and demonstrate control methods adapted to local conditions; and in the long-run, to develop an effective and comprehensive tuberculosis control program, and eliminate tuberculosis as a public health problem [60,]. WHO’s role was to provide advisory services by appointing expert consultants who would reside in Korea to assist with planning, implementation, and evaluation of the national program, as well as provide fellowships for Korean staff in nearby countries [61,]. Over the next few months, WHO appointed a Senior Tuberculosis Advisor and a Public Health Nurse as permanent staff, and assigned three short-term consultants for bacteriology, X-ray, and statistics. As WHO’s regional advisor, Tao was to return on a regular basis [62].

By the time Tao made his next visit in April 1962, the political landscape in Korea had much changed with the military coup ousting the civilian government in the previous year. The new government led by General Park Chung Hee immediately announced the Five-Year Economic Development Plan, and began to lay out public health programs in conjunction with economic development, such as family planning campaigns (DiMoia, 2013: 109-144). Diseases of high prevalence that threatened the wellbeing of the labor force received serious attention, including tuberculosis and parasitism among others (Jung et al., 2016: 167-203). Of the two, tuberculosis was especially linked with poverty. It was a manifestation of destitute conditions, but was also thought as a cause for them. In general, the military government was keen on developing public health programs to shore up their legitimacy.

On his second visit in 1962, Tao noticed notable changes made under these circumstances. He was “impressed by the cleanliness of the streets, the orderliness of the traffic, the stability of currency, the virtual absence of foreign commodities in the market, and the high working morale of the civil servants.” A new Minister of Health and Social Affairs, a doctor with military background, had been appointed (Lee, Y., 2018: 44-45), and the Ministry had undergone yet another reorganization. Most importantly, the Bureau of Preventive Medicine was replaced with the Bureau of Public Health, which newly included the Section of Chronic Disease Control. Administrative shifts in the provincial government finally removed the Provincial Bureaus of Public Health and Welfare from the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education and Social Affairs.

Besides the administrative restructuring, there were substantial advancements in the health sector. Expenditure for health had increased from 0.45 percent to 0.7 percent of the total government budget, including a radical raise in remunerations for high ranking officials. In just one year, more than twenty peripheral health centers were built anew to give 100 functioning centers, with plans for at least 80 more. In fact, the government was planning to announce a completely revised Public Health Center Law in the coming month. The revised law would place health centers under the supervision of not the provincial and city municipality, but each city, gun and ku, allowing for more localized operations and supervision. The official responsibilities and functions of the health centers would double, as they were to serve more than preventive purposes but become central to ensuring the health of the local communities by providing comprehensive health and medical services. Moreover, in order to address the challenge of recruiting medical personnel in remote areas including doctorless villages, the government revived the Doctors Mobilization Act that could force physicians to serve the government in place of their military duty (KPHA, 2014: 76-78; Park, S., 2018). The military government’s immense administrative capacity in mobilizing public resources and its interests in the public health sector were clearly conveyed to Tao and WHO [63].

Atop these general changes, Tao found that some of his initial recommendations for tuberculosis had already been implemented. For instance, a Tuberculosis Control Body had been established under the Ministry, staffed with two medical officers, one bacteriologist, a public health nurse, and several support staff. In addition, a Tuberculosis Control Coordination Committee was to be convened, bringing together all domestic and international agencies concerned with tuberculosis, including the Korean Church World Services, the National Medical Center, the National Tuberculosis Association, and the US Agency for International Development [64]. These were among the high priorities in the Plan of Operations.

The functions of the Body and the Committee were, in essence, to centralize the operations of the national program in both administrative and technical aspects of tuberculosis control. WHO’s role was then to “to help the Ministry to take up the leadership in directing the programme.”

Although there were “numerous agencies, voluntary as well as official, doing tuberculosis work in Korea, Tao contended that the responsibility of coordinating and standardizing the activities should be in the hands of the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. WHO’s service would be “primarily to assist the Ministry to unify the policy and to standardize the methods of approach.” [65] In turn, the role and responsibilities of the National Tuberculosis Control Body would be “the main central directing and executing agency in the National Government of the Republic of Korea”:

The Body will be responsible for planning, organizing, executing, supervising, and evaluating the programme… Therefore, in view of its important tasks in direction the national programme, authority in technical as well as administrative matters has to be granted to the Tuberculosis Control Body and its budget made independent. Strong support of this principle has been promised by the Minister [66].

Under these arrangements and understandings, the Ministry was poised to play more than an administrative role and become more involved in technical operations. For an effective WHO-assisted national program for tuberculosis, a powerful and competent Tuberculosis Control Body was less of a recommendation than a precondition. The Ministry appointed its Head of Preventive Medicine Section, Choi Don Won, as the Chief Medical Officer for the Tuberculosis Control Body. Choi had suffered from tuberculosis while he was a medical student, and had devoted his career to tuberculosis and even opened a small tuberculosis hospital in his hometown (KNTA, 1998: 473-474, 1009). A doctor-turned-bureaucrat, Choi possessed technical knowledge as well as practical experience with tuberculosis control. His appointment reflected what the government and WHO expected from the Tuberculosis Control Body.

WHO’s long-range plans, however, were more than the centralization of tuberculosis control. Centralized direction and execution through the Body was only provisional, until the provincial governments and municipalities became better equipped and more qualified personnel became available. The ultimate goal was to implement technical control measures through local health centers. Tao made no direct reference to ‘horizontal’ methods or the ‘community’ approach, but the emphasis on tuberculosis service delivery through general health systems was clearly evident throughout his reports. With the new government’s drive for local health services, Tao no longer had to stress on the matter of establishing rural health networks. Instead, he paid close attention to technical practices. Tao’s report comprised of lengthy and detailed deliberations on the local staffs’ technical practices for vaccination, case-finding, and domiciliary treatment, and how they should be improved. In addition, he also paid close attention to training programs for health workers and demonstration centers. These were the sites that determined the quality of technical measures for people, and where standardization must be observed.

Tao’s concern over the deep involvement of a non-governmental agency in tuberculosis control was also noticeable. The Korea National Tuberculosis Association had been an indispensable constituent of the infrastructure with its physical and financial resources, manpower, and technical expertise. Generally, in Geneva, WHO’s Technical Committee on Tuberculosis acknowledged the importance of voluntary organizations and fully encouraged their involvement, but considered them only as “an important means of obtaining the cooperation of the public.” [67]

This division of labor, in tandem with the role of local health centers, under WHO’s framework was a stark contrast from Korea’s existing arrangements, where voluntary organizations were central to healthcare delivery. The Association was involved in all aspects of the Ministry’s national program since the early 1950s, and the government relied heavily on its expertise. This voluntary organization operated its own clinics and provided treatment and vaccinations, mobile units for mass case-finding, laboratories for culture work, and trained health workers before these missions were transferred to local health units. It also carried out massive public campaigns for raising awareness, published general educational material, and maintained an academic society both domestically and internationally. The funds it raised through public campaigns attested to both its popularity and ability to independently sustain its operations. In 1963, it collected nearly 60 million Korean won—almost 90 percent of the government’s budget for tuberculosis that year (KNTA, 1974: 137).

Tao’s statements regarding the role of the Association became more explicit as WHO’s assistance progressed. Upon his initial survey, he applauded the Association for its work in areas where even the government had been unable to accomplish, with a brief note that all its activities must be coordinated with the Ministry [68,]. The following year, he admitted that the Association’s service and support for the government was “impressive and admirable,” but warned that its active participation should be considered temporary and not reduce the Ministry’s responsibilities [69,]. In 1963, he straightforwardly points out that the activities sponsored by the Association “should actually be the government’s responsibility,” which the government must take over as soon as possible [70,]. WHO and the Association would later disagree strongly on certain technical aspects of tuberculosis control (Ku, 2005: 42-57), but Tao had maintained a positive outlook. He expected the Association’s cooperation to continue but in a different capacity.

By August 1963, less than two years since the signing of the Plan of Operations, Korea’s infrastructure for tuberculosis control had made “tremendous progress.” National budget for tuberculosis increased to 71 million won (from 55 million in 1961) [71,], and all nine provincial governments operated BCG and X-ray teams with plans to establish tuberculosis laboratories and assign medical supervisors to coordinate tuberculosis activities in each province. There were now 189 health centers in operation, each appointed with a tuberculosis nurse and follow-up workers to carry out BCG vaccinations, microscopic examinations of sputum, follow-up with patients on ambulatory chemotherapy, and manage the registry. Tao observed that many of the workers had been enthusiastic and working hard “under the capable and devoted leadership of the Tuberculosis Control Body,” and he noted that he was “indeed proud of the project, and gratified that the World Health Organization has been able to provide some assistance,” further acknowledging the advancements made in the short period. Driven by the government’s executive ability and emphasis on the health of the labor force under the first Five-Year Economic Development Plan, Tao witnessed the expedient establishment of a tuberculosis control program buttressed by a burgeoning public health infrastructure [72].

6. Conclusion

The concept of public health was introduced to South Korea by the U.S. military government in the years between 1945 and 1948, but the infrastructure for dealing with specific public health issues underwent important changes during the politically and socially tumultuous decades of the 1950s and 1960s. This paper argues that the role played by WHO for Korea’s public health should be understood within this historical circumstance as well as within the conceptual developments taking place at WHO headquarters regarding its global approach to tuberculosis control. WHO consultants consistently pointed out the administrative problem and the lack of public health infrastructure that could effectively link the central and regional health units. The report written by Macdonald’s team in 1952 cautioned strongly against this shortfall, and emphasized how strengthening the existing health dispensaries into health units (or centers) could benefit the control of different diseases and health issues facing Korea, not to mention tuberculosis which had been pinpointed as the most serious and economically burdensome disease by Leppo in 1950.

Macdonald’s proposals to introduce the horizontal approach seemed to fall on deaf ears as the Korean government had neither the political will nor the administrative and technical capacity to implement the idea in the 1950s. The gap was filled instead by voluntary organizations, most notably KNTA, which assumed the responsibilities and functions of the government. In other words, rather than introducing a horizontal approach to public health by expanding general health services, the central government struggled to maintain an administrative organization with a coherent channel of communication and responsibility through to the local government. It also continued to explore possibilities of expanding sanatoria and hospital beds and address tuberculosis as a clinical or social problem, and tuberculosis control continued to resemble the vertical, disease-specific approach with KNTA playing a major role as part of the nation’s public health infrastructure.

WHO’s 1962 Plan of Operations, the formal agreement indicating the beginning of WHO’s technical assistance for South Korea’s national tuberculosis control that had been drafted following Tao’s survey report of 1961, marked an important turn for Korea in two ways. First, by then, WHO had been increasingly convinced of the value of the horizontal approach to tuberculosis control. The new community-based approach of domiciliary treatment, when applied in tandem with compulsory and regular patient monitoring, was a cost-effective means of dispensing anti-tuberculosis drugs, and had proven to be as effective as the traditional vertical approach. Second, unanticipated changes in the regime from a civilian to a military government led by a developmentalist junta had created an environment favorable for the expansion of the public health network. The horizontal approach was instrumental to the new administration, because it provided a good justification for its authoritarian policies—fostering the people’s health was a good means to secure a healthy workforce to advance the government’s priorities in economic development, and expanding the public health network also had the effect of strengthening the central government’s administrative power into the provincial and local governments. Within only a few years into its launch, WHO lauded the Korean case as a success, unlike any other program in the entire Western Pacific region. The treatment of tuberculosis was no longer left to individuals, but it was considered the state’s public health responsibility. New governing offices dedicated to tuberculosis were established within the Ministry and provincial governments, and tuberculosis services were delivered through government-funded local health centers. WHO did attain its objective to centralize tuberculosis control in Korea, but only insofar as Korea’s pre-existing infrastructural and political affordances allowed.

Notes

“ A Helping Hand from the World Health Organization” [Segye-bogeon-gigu-seo wonjo-ui son], Donga-Ilbo, 17 December 1961. This article transcribes Korean phrases using the system of Revised Romanization of Korean over the McCune-Reischauer system.

“Pulmonary Tuberculosis Increases Several-fold Compared to Pre-Liberation,” [Pyekyulhaek haebanngjeon-boda subae jeungga haebanngjeon-boda subae jeungga], Kyunghyang-Shinmun, 02 December 1949. See also “Christmas Seals for Tuberculosis Eradication” [Kyulhaek-bangmyeol-e keuriseumaseu ssil deungjang deungjang], Donga-Ilbo, 18 December 1949.

“Danger Signal for National Health!! Two Million Infected with Tuberculosis” [Gukminbogun-e juksinho!! Kyulhaek-bogyun ibaengman], Donga-Ilbo, 22 May 1949.

“Prospects for Joining United Nations Division of Social Welfare Shed Great Ray of Hope,” [Gungnyeon-sahoe-saeopbu-e hanguk-gaip-gamang gungmin-bogeon-e ildae-seogwang], Donga-Ilbo, 23 November 1949; “Lamentable National Health,” [Hansim-seureoun gungmin-bogeon gungmin-bogeon], Donga-Ilbo, 29 July 1949.

See WHO, 70 Years Working Together for Health: World Health Organization and the Republic of Korea (WHO, 2016).

In the body of this paper, the Korean names are presented with the family name placed before the given name, unless the names are commonly used in the other way. For example, the family name of “Lee Sun Ho” is Lee, while that of “Jane S. Kim” is Kim.

For a broader reading on the debate between clinical and public health approaches in tuberculosis control, see Sunil Amrith, Decolonizing International Health: India and Southeast Asia, 1930-65 (Springer, 2006): 156-160; Christian McMillen, Discovering Tuberculosis: A Global History, 1900 to the Present (Yale University Press, 2015): 186-201; Randall Packard, A History of Global Health: Interventions Into the Lives of Other Peoples (JHU Press, 2016): 105-131.

According to A. E. Birn, the rift between the two approaches became increasingly marked as the debate progressed to extrapolate the vertical versus horizontal dichotomy onto debates about technical versus social, centrally driven versus locally defined, disease-based versus health-based, individually versus collectively-oriented, doctor-centred versus healer- centred versus community-centred, and so on. See Anne-Emmanuelle Birn, “The Stages of International (Global) Health: Histories of Success or Success of History?” Global Public Health 4 no. 1 (2009): 50-68.

See also “Declaration of Alma-Ata, International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September, 1978,” available at http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf, accessed March 26, 2018.

“Dr. Erkki Leppo Arrives in City from Switzerland,” The Daily News, Ludington, Michigan, 27 January 1950.

“Ministry of Social Affairs to Seek Assistance from WHO Regarding Two Million Tuberculosis Infections” [Sahoebu bogeonguk, kyulhaek-bogyunja ee-baekmanmyoung-e daehan daechaekgwa gwallyeonhae gukjae-bogeon-gigu-e wonjo yocheong], Donga-Ilbo, 22 May 1949.

“Tuberculosis in South Korea,” p. 2, WP/RC2/2, Project Files Korea-1201, WHO Archives, Geneva (henceforth simply WHO Archives).

Contents of Leppo’s report were later published in prominent international journals, such as Tubercle and the British Medical Journal.

“Tuberculosis in South Korea,” p. 2, WHO/TBC/29, WHO Archives.

For a debate on the notion of modernity in medicine in Korea prior to the colonial period, see Dong-won Shin, “Hygiene, Medicine, and Modernity in Korea, 1876-1910,” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal (EASTS) 3-1 (2009): 5-26. The Japanese colonial government demonstrated an especially repressive and dominating approach, and sought to foreground western medicine and eliminate native Koreanness by demeaning traditional medical practices. For characteristics of Japanese colonial medicine in contrast to that of the British Empire in India, see Yunjae Park, “Medical Policies toward Indigenous Medicine in Colonial Korea and India,” Korea Journal 46-1 (2006): 198-224.

The implications of this approach to public health become more conspicuous when juxtaposed with the path taken in North Korea, where government also abolished the colonial wisaeng police and adopted the term bogeon in its bureaucratic organization, but it completely revamped the system by prioritizing preventive medicine and nationalizing medical facilities. See Dong-won Shin (2015): 95-100.

Korean translation of original speech available from Chai C. Choi, The American Medicine in Korean Medical History (Younglim Cardinal, 1996): 187-190, English quote from Dong-won Shin (2015): 102.

“Public Health in Korea,” pp. 1, 6. Submitted by Delegate of Korea for Second Session of Regional Committee, 18th to 21st September 1951, WHO Western Pacific Regional Office, WP/RC2/2, WHO Archives.

“Tuberculosis in South Korea,” pp. 9-13, WHO/TBC/29, WHO Archives.

“Tuberculosis in South Korea,” p. 10, WHO/TBC/29, WHO Archives.

“Tuberculosis in South Korea,” p. 12, WHO/TBC/29, WHO Archives.

“Public Health in Korea,” p. 12, S-0526-0337-0001-00002-UC, United Nations Archives New York (henceforth simply UNA).

Namely, the National Tuberculosis Sanatorium, the Transportation Ministry’s Sanatorium in Masan, and the Korean Red Cross Sanatorium in Incheon.

“Public Health in Korea,” p. 15, WP/RC2/2, WHO Archives.

“Public Health in Korea,” pp. 21-22, WP/RC2/2, WHO Archives.

WHO, Official Records 30 (1951), p. 136.

WHO, Official Records 30 (1951), p. 3.

UNCACK was later renamed the Korean Civil Assistance Command (KCAC) when the US Army took over the functions. See WHO, “Relations with United Nations Korean Reconstruction Agency,” A5/61, Fifteenth World Health Assembly, 16 May 1952. See also Edward S. Mason, et al., The Economic and Social Modernization of the Republic of Korea (Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Asia Center, 1980).

“Summary of the Public Health and Welfare Section’s Activities in Korea,” 9 July 1952, S-0526-0337-0001-00002-UC, UNA.

WHO, Official Records 30 (1951), p. 40.

Although officially UN bodies, CRIK, and UNKRA were effectively agencies representing and extending US interest and influence on South Korea. CRIK operated almost entirely on US government funding, and UNCACK operations were transferred to the US Army after the end of hostilities (and was renamed the Korean Civil Assistance Command, KCAC). Activities of UNKRA were also heavily contingent on US foreign policy for Korea. For more information, see Mahn Je Kim and Dwight H Perkins, The Economic and Social Modernization of the Republic of Korea (Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1980): 179; Gene M. Lyons, “American Policy and the United Nations’ Program for Korean Reconstruction” International Organization 12-2 (1958): 180-192.

Its organization structure can be found at https://unarchives.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/unkra_0182001.jpg (last accessed 30 August, 2018).

UNKRA, “Relief Program -Provision of Medical Facilities and Supplies: Mobile Clinics-General” S-0526- 0027-0001-00001 UC, UNA.

Letter from Assistant Secretary of State of the USA to Agent General of UNKRA, Appendix C, 11 July 1951, S-0526-0337-0001-00003-UC, UNA.

UNCACK, “Preliminary Statement on Planning for the Rehabilitation of ROK,” 9 July 1952, S-0526-0337-0001-00002-UC, UNA.

The timing of this WHO/UNKRA health planning mission has sparked contention by scholars such as Jane Kim regarding the political nature of the mission, as it coincides with the accusations made by the Chinese and North Korean governments against the US for the possible use of biological weapons. A letter from WHO’s Director of Administrative Management and Personnel Division to UNKRA Chief of Office in early June 1952 does suggest that WHO and UNKRA proceeded in a hurried and discreet manner, with “no desire to be too formal over this matter” in initiating preparations for the mission. “Letter of Agreement between WHO and UNKRA Regarding the Development of a Five-Year Public Health Program as Part of the UNKRA Five-Year Programme for the Rehabilitation of Korea” 10 June 1952, Second Generation Files, PH 2-5/49, WHO Archives.

Letter from Deputy Agent General, UNKRA to Members of the WHO Consultant Team, 4 August 1952, S-0526-0337-0001-00003-UC, UNA.

“Report of the WHO/UNKRA Health Planning Mission in Korea,” 26 November 1952, pp. 8-16, S-0526-0098-0004-00001-UC, UNA (henceforth simply “WHO/UNKRA Report”).

WHO/UNKRA Report, p. 5.

WHO/UNKRA Report, p. 12.

WHO/UNKRA Report, p. 30.

WHO/UNKRA Report, p. 55.

WHO/UNKRA Report, pp. 61-65.

WHO/UNKRA Report, p. 35.

The National Medical Center is referred to as a model case in South Korean development history due to its smooth operation despite the many actors involved in its organization and management, and continues to serve as a major public hospital until this day. See F. Schjander and J. Bjørnsson, The National Medical Center in Korea: A Scandinavian Contribution to Medical Training and Health Development, 1958-1968, Scandinavian University Books (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1971); K-Developedia, s.v. “Establishment of the Korea Medical Center,” KDI School. http://kdevelopedia.org. Accessed, 23 September 2018.

The head of the tuberculosis section, Dr. T. Wessel Aas, considered expanding the Center’s small program by seeking assistance to WHO. Letter from T. Wessel Aas, M.D. to the Governing Board of the National Medical Center in Korea, forwarded to the Minister of Health and Social Affairs, Seoul, 16 November 1959, REF: BA0127547, Korea National Archives, Daejeon.

For a closer reading on AKF’s involvement in South Korea, see So Ra Lee, “Activity and Historical Role of American-Korean Foundation (1952-1955),” PhD diss., Seoul National University, 2015; Bong-Beom Lee, “American Korean Foundation, the Cold War and Downward Solidarity of Korea-U.S.,” Korean Studies 43 (2016): 205-59. AKF’s work was propagated to the American public through popular magazines, such as Life. See Howard A. Rusk, A World to Care For: The Autobiography of Howard A. Rusk, M.D. (New York: Random House, 1972); Howard A. Rusk, “Voice from Korea: ‘Won’t You Help Us Off Our Knees?,’” Life, 7 June 1954; Editorial, “Helping Koreans Help Themselves,” Life, 12 October 1953.

For a closer look at AKF’s health activities, see Young Hun Kwon, “Activity and Effect of American-Korean Foundation in Public Health (1953-1955)” Master’s thesis, Yonsei University, 2017.

“Annual Report on AKF Tuberculosis Control Project Activities Covering a Year from September 1953 to August 1954,” 9 September 1954, pp. 6, DC/TB/C/2, Second Generation Files, WHO Archives.

Han Eung Soo, author of the report, described the Association’s organizational structure and mandates as having been modelled after the U.S. National Tuberculosis Association. “Annual Report on AKF Tuberculosis Control Project Activities Covering a Year from September 1953 to August 1954,” 9 September 1954, pp. 4, DC/TB/C/2, Second Generation Files, WHO Archives.

Akin to this, The Foundation funded additional voluntary operations by the Korea Church World Service. See Kwon, 2017: 56.

Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, “Annual Report on Tuberculosis Control” (1959): 22.

Han resigned from his position at the Ministry following the fall of the Rhee administration, to which he was a close ally, and joined WHO’s Western Pacific Regional Office. During the 1960s, we he oversaw the implementation of WHO’s community approach in Sri Lanka. See “Interview with Han Eung Soo,” in A History of Tuberculosis in Korea (KNTA: 1998), p. 995; and Margaret Jones, “Policy Innovation and Policy Pathways: Tuberculosis Control in Sri Lanka, 1948-1990,” Medical History 60-4 (2016): 514-33.

WPRO, “Report on a Field Visit to Korea: 22-29 March 1961” by J. C. Tao (henceforth simply Tao, 1961), pp. 12, WPR/TB/FR/15, WHO Library, Geneva.

WHO, The First Ten Years of the World Health Organization (WHO, 1958), pp. 188-197.

Madras Tuberculosis Chemotherapy Centre, “A Concurrent Comparison of Home and Sanatorium Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in South India.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 21-1 (1959): 468-76; Madras Tuberculosis Chemotherapy Centre, “A Concurrent Comparison of Home and Sanatorium Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in South India.” Tubercle 40-6 (1959): 468-76.

WHO, International Work in Tuberculosis, 1948-1964 (WHO, 1965), p. 16.

WHO, Seventh Report of the Technical Committee on Tuberculosis, Technical Report Series No. 195 (1960), p. 13.

Tao, 1961, pp. 13-18.

Elimination of tuberculosis as a public health program referred to a prevalence rate of less than 1 percent of natural reactors to tuberculin among children aged 14 and under. The estimated rate at the time was as high as 65 percent.

Plan of Operations for a National Tuberculosis Control Programme in the Republic of Korea, signed by WHO on 28 December 1961, and the Korean Government on 31 January 1962, WPR/422/61, Jacket 1-3, Project Files Korea-1201, WHO Archives.

WPRO, “Report on a Field Visit to Korea: 30 April-10 May 1962” by J. C. Tao, (henceforth simply Tao, 1962), pp. 6, WPR/286/62, Jacket 1-3, Project Files Korea-1201, WHO Archives.

Tao, 1962, pp. 1-4.

Tao, 1962, p. 6.

Tao, 1962, p. 11.

Tao, 1962, p. 11.

WHO, Seventh Report of the Technical Committee on Tuberculosis, Technical Report Series No. 195 (1960), p. 17.

Tao, 1961, p. 18.

Tao, 1962, p. 13.

WPRO, “Report on a Field Visit to Korea: 16 to 22 July 1963” by J. C. Tao, (henceforth simply Tao, 1963), p. 7, WPR/309/63, Jacket 1-3, Project Files Korea-1201, WHO Archives.

Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, “Annual Report on Tuberculosis Control” (1960): 17.

Tao, 1963, p. 9.